Not at all.

Whether you approach your practice as a martial sport or a martial art, defeating your opponent can be a useful measure of your ability. However, it’s the wrong place to be looking until a fair ways down the path of setting a martial foundation.

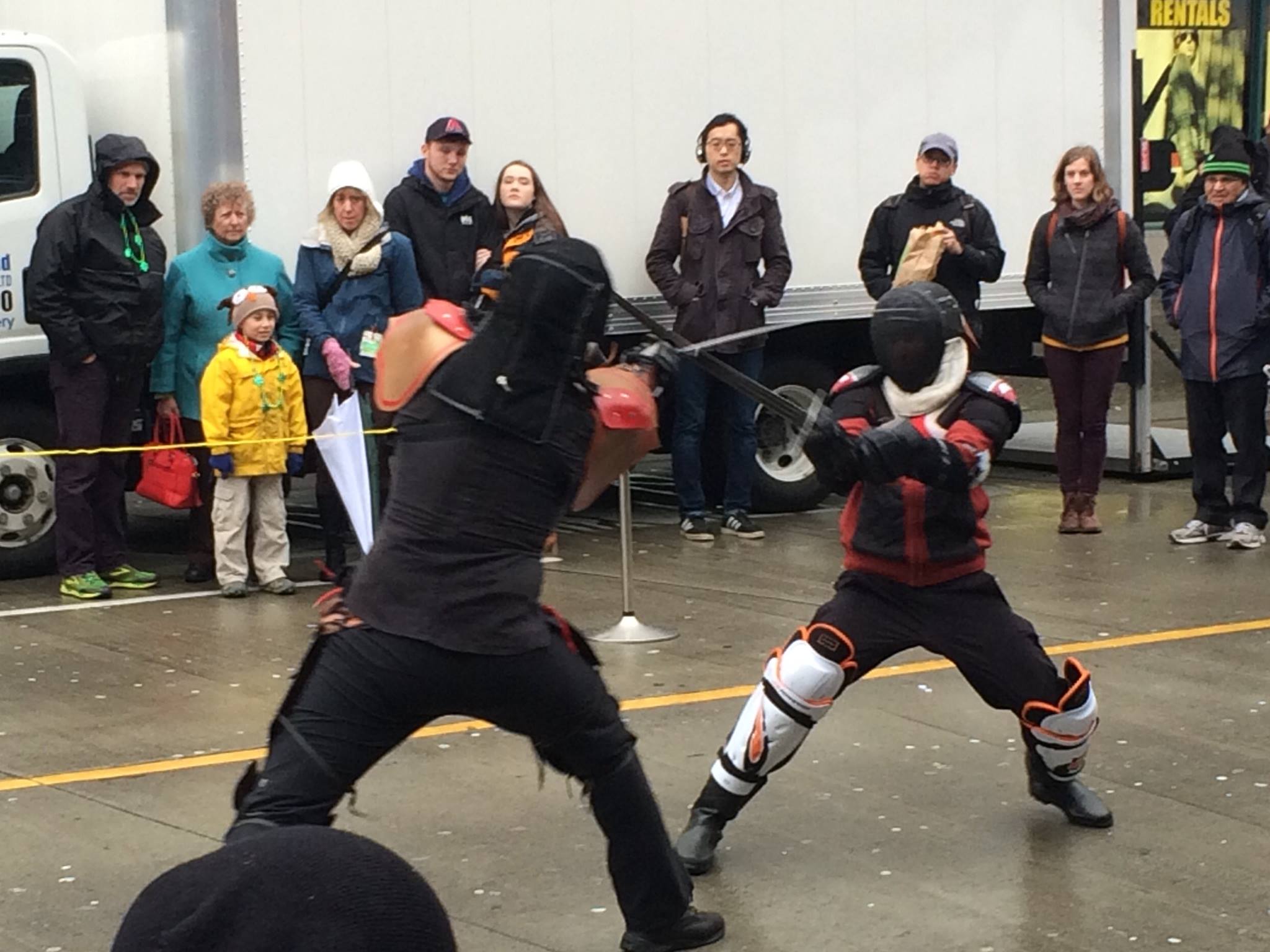

There are many techniques, tricks, and traps one can employ, with relatively little practice, that will score you some hits on mediocre fencers. When I see a student put their focus on winning, instead of martial development, I often see these come to the fore. Whether it’s aggressive flailing, chaos and randomness, or even some well-honed gimmicks, you can score some quick points early on. The challenge is that none of these approaches provide a base for later excellence. An 80% win/loss ratio, or an even more martially sound 100% win/loss ratio (no one wants to die right?), require long-term thinking and investment to achieve. There is no way to use flailing and gimmicks as the foundation required for high-level effectiveness.

Getting out there and mixing it up can be fun, and I don’t want to discourage anyone from having genuine fun as part of their practice. However, I want my students to not confuse winning with learning. Learning by its very nature requires a lot of losing. You must work on things that are uncomfortable, new, and unpracticed, put them under pressure and have them fail and then repeat. To maintain the resilience required for this process, it’s important to target your goals on an outcome other than winning.

Here are some things I recommend targeting in sparring that will help you set a stronger foundation:

- Form under pressure. Work on staying low and balanced. Practice crisp and fluid movement between postures. Make as many attempts at techniques from class as possible (they don’t need to be successful).

- Relaxation and flow. Combat puts psychological and physical pressures on you that can move you into the fight or flight response. From this space, reactions can become exaggerated and chaotic. Focusing on staying relaxed, flowing from action to action, and staying in motion can help lay the ground work for much more effective fencing later.

- Perception and awareness. It takes practice and repetition to remember what happened in a fight, yet the ability to recall, analyze, and use what you’ve learned is well worth the investment. Set a personal objective not around winning but around recall.

In the early stages of your learning, and by early I can mean during your first few years, focused practice is far more valuable than winning, in general. If you find measurable objectives motivating, consider some objectives like these:

- Number of fencing passes fought in a period of time. (If you put your focus on the ideas I’ve shared above, these passes can be very valuable.)

- Time spent in drilling, number of classes attended, number of technique repetitions.

- Number of losses — how many fights can you lose in this sparring session? Even as you start to get more successful, this type of objective can help you push yourself into new territories of learning.

Make sure that your training environment suits your personal objectives and goals. Approach sparring thoughtfully and reasonably and it can be a rewarding, engaging, and fun place to build your art and yourself.