Many martial traditions, including ours, use martial forms (series of attacks and defences for solo or partnered practice) to help train martial precision, flow, and fitness.

Having a form that you can practice without a training partner provides structure for improving and maintaining your martial ability when you don’t have the option of training with someone else. Forms also provide an avenue for exploring and enjoying the internal side of practice that is not about competition, defence, or other kinds of partner interaction.

Learning a martial form can be but fun and frustrating. It is not necessarily a fast process. It requires comprehension, memorization, precision, and good mechanics. Yet, we cannot achieve all of these things at once, especially when we’re new. Here is the process I advocate for going from nothing to something with a martial form, represented by the acronym SKIL:

- Sequence

- Kinetics

- Intent

- Look

Sequence

First, memorize the order of actions within the form. The goal here is specifically to learn the sequence—not do the actions correctly. It can be cognitively overwhelming to try not only to learn what comes next but also correct hip alignment, sword path, body alignment, etc. So, simplify what you’re learning.

Make sure you’re doing essentially the right shape of the movements (i.e., basic cut path, correct foot to step with) but don’t worry at all about doing them well. Your goal is to be able to move through each action in the sequence smoothly without pausing to think, “What now?” Actors use a process to memorize chunks of a script where they repeat sections of dialog over and over again without any punctuation or emotional emphasis.

The goal is to internalize the script so thoroughly that they can free their mind to bring in proper intent, emotion, and physicality without having to devote mental resources to searching for words. Interestingly enough this process is often called “doing Italians”. If you’re working with a particularly large martial form, break it into chunks and go through the four stages of SKIL with each part individually.

Kinetics

Once you have memorized your sequence so that the flow of movements comes effortlessly from memory, it’s time to start devoting some mental energy to doing the moves correctly. When examining the kinetics or mechanics of a form, it’s important to seek precision before speed. Refer to my article Crispness, Smoothness, then Quickness for a detailed breakdown of how to do this effectively.

Here it can be a better use of your time to pull out specific, challenging, moves from the form and practice them individually. Then when you feel you’ve made forward progress, bring the corrected mechanic back within the larger context of the sequence.

Intent

What is the purpose of each movement in the form? How do the moves connect with one another? What’s really happening? Kinetics are largely driven by intent, so once you have the mechanical form in place it is important to bring in purpose.

I recommend assessing your form in two- to four-technique movement chunks. Work through them with a partner to consider how they are connected and applied combatively. Focus the intent of striking with proper breathing and grounding. Ensure that you are generating the correct force and flow from action to action. Are you cutting through your opponent’s weapon? Is this action a deception? How important is the efficiency to the next movement vs. power generation?

Look

How an art “looks”, or its aesthetic, is often as foundational to its practice as its effectiveness at accomplishing martial objectives. Certainly within noble European martial traditions, how you presented yourself was equally as important as kicking butt, if not more so. If you were to succeed martially in a duel or display while appearing cowardly, oafish, or inelegant it would be a huge social failure—of perhaps greater consequence than death!

There is also much to be learned about an art’s mechanics and methods through emulating its look. There are many aspects of body alignment and bearing that seemed completely artificial when I first began the study of Italian arts. However, I later came to understand them as fundamental to accomplishing the art’s combative goals.

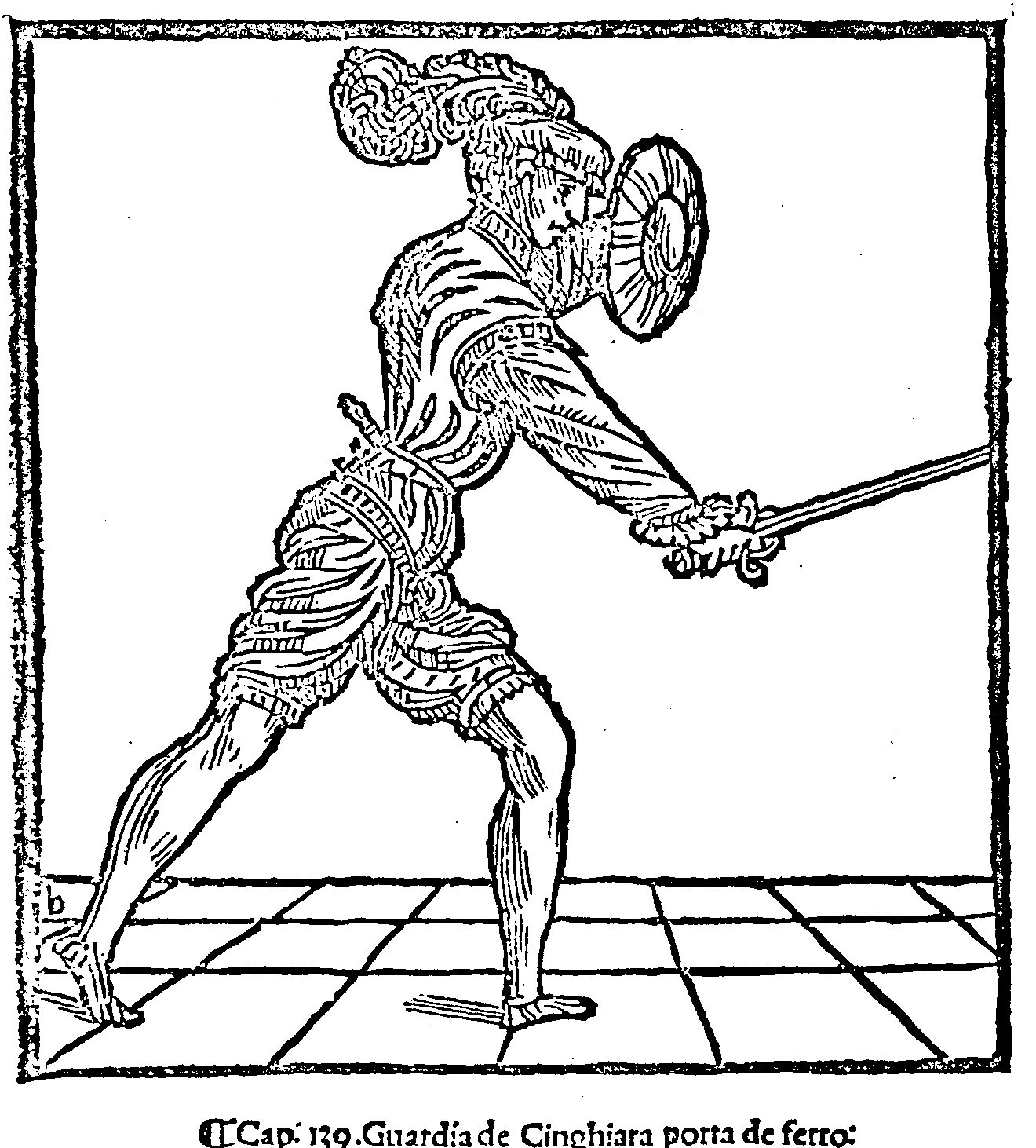

If you’re interested to try this process out, I recommend the sword and buckler forms presented in many of the Bolognese sources such as Achille Marozzo and Antonio Manciolino. We have a series of video lessons on the first parts of Marozzo’s first and second assault on DuelloTV.

Enjoy your solo training!