Recently, I began a blog series answering, in broad form, why we teach the rapier and longsword as part of one system at Academie Duello. I started in the first post by looking at the historical precedent for multi-weapon study that spans many original fighting manuals from both the medieval period and the Renaissance, as well as across many nationalities. In this post, I want to dive into what I feel are the benefits we get from including rapier within our approach to Italian martial arts.

A Unified System of Weapons and Strategy

The complete system at Academie Duello includes practice with unarmed, dagger, longsword, sidesword, rapier, and polearms, along with various secondaries such as parrying daggers and shields. (It’s important to note that we don’t teach them all at once. Students start with rapier or longsword along with foundational wrestling. They then gradually progress through all of the other weapons through years of study).

We use a unified approach across all of our disciplines that comes from the late medieval and renaissance martial traditions of Northern Italy. We use a common terminology for all weapons, as well as shared mechanical, tactical, and strategic principles. Although there are reasons to hold your body in different ways with different weapons, and certain weapons predispose themselves to certain tactics, they are all understood within the same art.

From a learning perspective, this allows each weapon to act as a learning device for the student, sharing with them the principles, tactics, and approaches for which it is the best exemplar. A student can then take those lessons and apply them to the other disciplines in the art, or even an unfamiliar weapon. They can also more easily assess and face diverse martial situations.

The Rapier, Master of Geometry

One of the rapier’s primary methods for defence is simply the threat of its point. Unlike many other weapons, where combatants frequently approach with the weapon withdrawn (or chambered), with the rapier it’s best to extend it from the start.

By keeping the sharp tip between you and your enemy, the length of the weapon makes it dangerous for an opponent to approach without first addressing it. If they try to clear the point of the rapier by beating it aside, a nimble fencer can avoid the beat and use that moment to strike with a thrust.

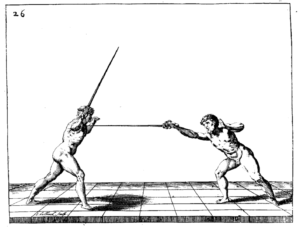

This combination of threat and dexterity forces the opponent to enter into the same game. At our school, we use the term “Gioco Stretto” or “Narrow Play” to refer to this situation where the threat of the opponent’s point is imminent and you must engage their weapon with your own. You do this by putting your sword in close proximity to the opponent’s or into direct contact. From there you need to use superior position to ensure that you can keep your sword point on-line and threatening while forcing your opponent’s point away.

“Gioco Stretto” shown at rapier from the manual of Ridolfo Capo Ferro (1606)

In gioco stretto, small movements and having a better sword position (one that applies leverage and body structure in your favour) are essential to victory. Making excessively large movements can be detrimental. Your actions must be discrete and contained. Because the weapons are frequently in contact, you must also develop a heightened sense of “feeling” through your sword so you can respond quickly and easily to adjustments to your opponent’s pressure.

Rapier fencers are required to develop an excellent sense of timing, distance, and tactility.

Body Position Optimization

Because the points are so close and the distances so short, how you shape and position your body is vital. Life or death can result because of a 2-inch change in sword position or a brief over-movement of your point.

Within the Italian tradition of fencing, there is a strong emphasis on aligning the body behind the sword to:

- reduce the targets the opponent can reach,

- minimize the amount your sword must move to protect the targets that are available, and,

- maximize your explosive speed and power.

You become extremely aware of how being structurally misaligned can impede your purpose, and how saving a few inches of movement can be the difference between delivering a successful strike or being struck.

The offensive and defensive posture. Used to withdraw potential targets and protect other vital targets behind the hilt.

Tempo & Theory

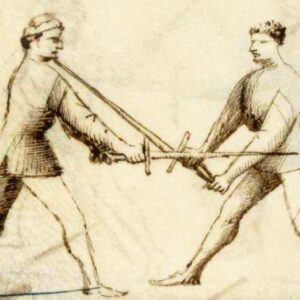

With its close proximity, the rapier also promotes a high level of awareness of opportunity. Both the opportunity to seize and maintain control but also the minute moments that an opponent offers you to strike them. Whether that’s as they step heedlessly into your range (primo tempo), as they briefly withdraw their sword (mezzo tempo), or while they attack into a position you can control (contro-tempo), the windows are small, requiring precision and mental readiness.

Exacting precision is reflected not only in the movement but in the language and theory of timing and distance that comes from traditional sources on rapier. Using this language and understanding across all disciplines can give you a greater ownership of exactly when to strike an opponent and how.

Striking an opponent while they lift their sword to cut (mezzo tempo). From the manual of Salvator Fabris (1606)

How this Relates to the Other Weapons

The principles of geometry, timing, and feel are essentially the same across weapons. What the rapier offers as a teacher is that it requires you spend a significant amount of time at gioco stretto where blade contact, precision movements, and a greater threat of the point are always present. The small tolerances for error and the nature of the weapon demand this. By practicing with the rapier you’re going to develop a much finer sense of these universally important ideas. When you find yourself in a similar situation with another weapon, the focused experience you’ve had from the rapier, and the fact that it is so demanding, will pay off greatly. It’s like how swinging multiple baseball bats at the same time helps a batter prepare themselves for swinging only a single bat at the plate. It makes the single bat feel lighter and easier to use.

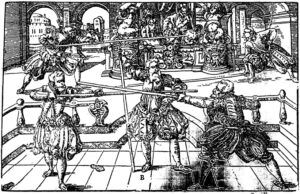

Even when using a weapon that might begin withdrawn, these point forward, “rapier-like”, situations still show up all the time. Whenever the weapons come together between you and your opponent (such as in an attack and parry) you’ll find yourself in gioco stretto and suddenly the same geometry, feeling, and timing become highly relevant.

A similar thrust with opposition in the manuals of Salvator Fabris (1606) and Fiore dei Liberi (1409).

Presenting the point is also a common strategic approach, even with more cutting oriented swords like the sidesword and longsword. Point presentation is also central to weapons like the staff and spear. All of these approaches are in gioco stretto and require the same tactical and mechanical knowledge that are applied with the rapier.

Rapier like postures in the use of the staff in the manual of Jaochim Meyer’s (~1560).

Even in the unarmed realm, these principles are still central. Bruce Lee incorporated his study of modern fencing into his own unarmed art, Jit Kun Do (Way of the Intercepting Fist), because it brought an approach to timing and line control he felt was absent from the other forms of boxing, both Eastern and Western, he had studied.

In the end, the shortest path between two points is a straight line, and in a one-on-one situation fighters that can control and master these straight paths will have a mastery over the fight regardless of the weapon.

Emphasizing Other Disciplines

Even with all its efficiency, understanding the art only through the lens of the rapier leaves you vulnerable to everything that happens outside of the realms of gioco stretto, single person combat, and fighting at long distances. In my next article in this series, I’ll explore how the study of the longsword can help you develop an awareness of gioco largo (the wide play), in-fighting, multi-directional combat, multi-opponent combat, and an appreciation for a whole new level of geometry in the cut.